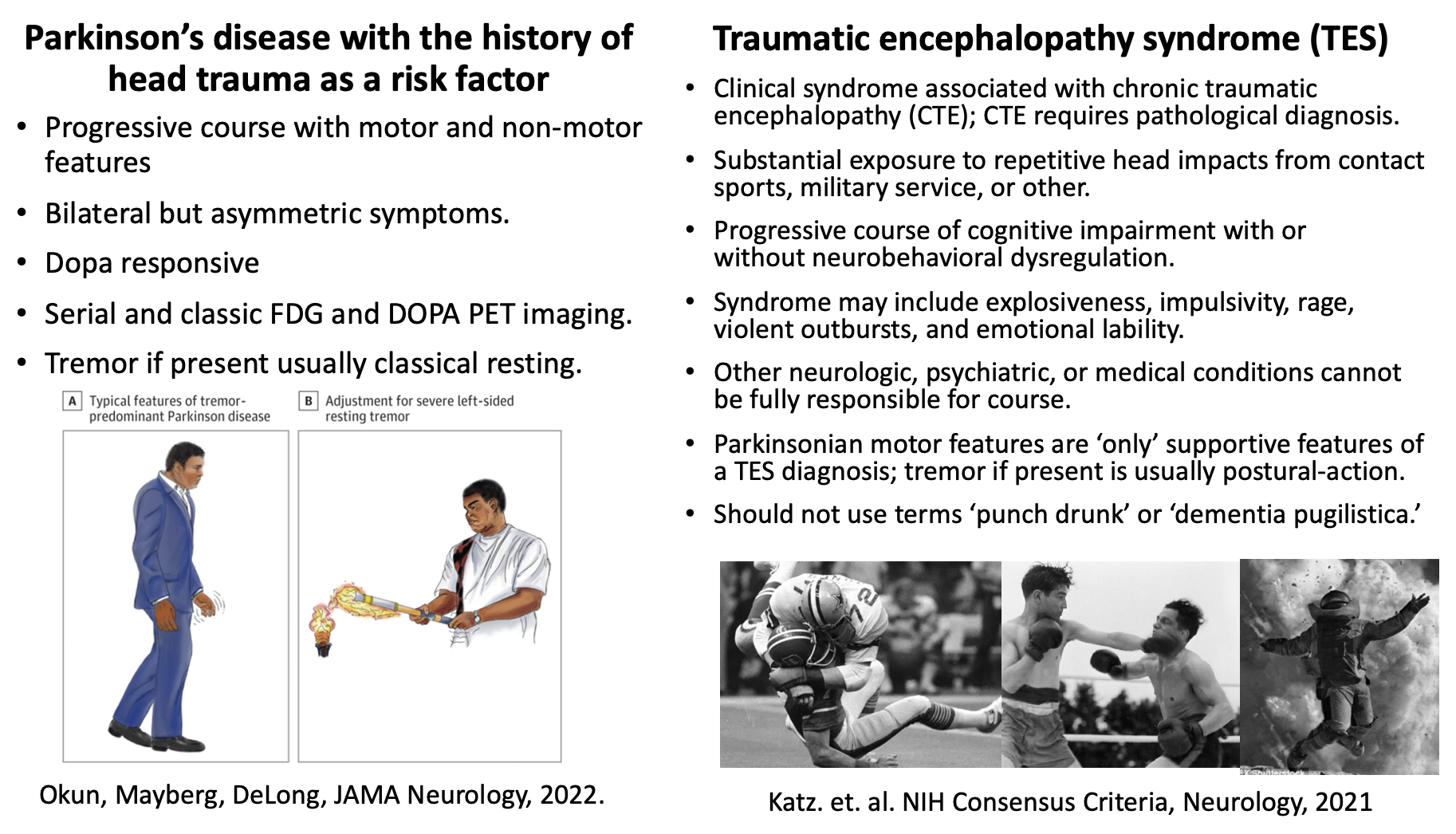

How to tell the difference(s) between Parkinson's + TBI vs. Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome

Recently, we published a paper in JAMA Neurology, Muhammad Ali and Young-Onset Idiopathic Parkinson Disease—The Missing Evidence. Questions have swirled about the degree to which Parkinson’s disease versus repeated hits to the head contributed to Muhammad Ali’s progressive tremor and cognitive impairment. This paper has opened an opportunity for us to teach a little bit about the differences between Parkinson’s disease + history of head injury vs. the traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. This is also an opportunity to re-examine and retire old and potentially inaccurate terms such as ‘dementia pugilistica’ and ‘punch drunk.’

What was Muhammad Ali’s clinical diagnosis?

Ali was followed for ~20 years at Emory University and the evidence supports a primary diagnosis of young-onset idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Ali had a 34+ year history of a progressive disorder which was dopamine responsive.

Why did some people assume Ali had a syndrome from ‘being punched’ in the boxing ring? The importance of the ‘Goldwater Rule.’

It is important that when a celebrity or public figure is ‘thought to have a medical diagnosis’ that we apply the ‘Goldwater Rule,’ which was introduced by the American Psychiatric Association. The rule was enacted following surveys (of practicing psychiatrists) and following speculation about Barry Goldwater’s mental health. Some historian believe the speculation impacted the 1964 presidential election.

The information on the Goldwater Rule is available publicly on the APA website:

‘APA President Daniel Blain, M.D., denounced the compilation (of opinions on Goldwater) as “a hodge-podge of the personal political opinions of selected psychiatrists speaking as individuals. … [T]he replies to the question have no scientific or medical validity whatsoever.”’

‘The APA in 1973 adopted Section 7.3 in the Principles of Medical Ethics with Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry, which became known as the ‘Goldwater Rule.’

‘The rule applies to public figures and states: “[I]t is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement” (see sidebar).’

In the Muhammad Ali case, permission was granted from the family to publish the article. The authors personally examined him and the data driving conclusions in his case were based on ~20 years of continuous follow-ups; plus additional brain imaging tests.

Why is it important to provide accurate details of Ali’s medical case?

Muhammad Ali is an important part of history, not just American history but in world history. Ali has been considered both iconic and influential. The history of his life, career and medical illness should be accurately preserved. The details of Ali’s medical history should only be shared following family permission which was granted for the JAMA Neurology article.

What were important clues that suggested Ali had young onset Parkinson’s disease?

Ali was responsive to the medication levodopa, which is the most commonly prescribed medication to treat Parkinson’s symptoms. An FDG-PET scan in 1997 showed progressive bilateral striatal hyperactivity, which is a Parkinson’s-related pattern. An F-DOPA PET scan revealed low striatal uptake also consistent with Parkinson’s. Repeated observations confirmed a prominent left-sided resting hand tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity; all were substantially improved when ‘on’ medications. Later in his disease course, Ali developed classical late-stage symptoms of idiopathic Parkinson’s, including stooped posture, shuffling steps, postural instability and falling. Serial neuropsychological testing showed progressive frontal and memory impairments consistent with classical Parkinson’s. The data all supported a ‘clinical’ diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s and not a diagnosis of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome from boxing related injury. There was no post-mortem examination conducted (religious reasons).

What is the ‘clinical syndrome’ associated with concussions and traumatic brain injury?

The clinical syndrome associated with concussions and traumatic brain injury is called traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES).

Substantial exposure to repetitive head impacts from contact sports, military service, or other.

Progressive course of cognitive impairment with or without neurobehavioral dysregulation.

The clinical syndrome may include explosiveness, impulsivity, rage, violent outbursts, and emotional lability.

Other neurologic, psychiatric, or medical conditions cannot be fully responsible for course.

Parkinsonian motor features are ‘only’ supportive features of a TES diagnosis; tremor if present is usually postural-action.

Should not use terms ‘punch drunk’ or ‘dementia pugilistica.’

In order to be diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which is the disorder we hear about a lot on the news in athletes, this diagnosis requires post-mortem (after death) brain tissue.

The comparison to concussion and brain injury was provided through assistance of Breton Asken PhD a neuropsychologist at the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases.

The parkinsonsecrets.com website blog is written and edited by Dr. Michael Okun and Dr. Indu Subramanian.

Jonny Acheson is our website artist. The art from the Ali post was completed by Erica Rodriguez.