Tips for integrating mindfulness in Parkinson's disease from author Christiane Wolf

Dr. Wolf website : https://www.christianewolf.com/

Who is Dr. Christiane Wolf?

Christiane Wolf is a mindfulness and compassion teacher who started her professional life as a Gynecologist at the University Hospital in Berlin, Germany where she was engaged in clinical work. She had fallen in love with the universality of the Buddhist teachings as a teenager and found that it helped her to stay sane through medical school and residency! In 2003 she moved with her husband and daughter to Los Angeles “for just one year” as she enjoyed her maternity leave. At that time, she met Trudy Goodman, an Insight meditation teacher, who had just started an organization she called “InsightLA” a few months prior. The two deeply connected and Christiane ended up training as an MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) teacher and learning to teach MBSR with Trudy. She became head consultant at the Greater Los Angeles Veterans Administration, realizing that the combination of medical and mindfulness training is a powerful combination to train fellow clinicians on how to teach mindfulness. In 2015 Dr. Wolfe and a colleague from the VA, Dr. Greg Serpa, published the book “A Clinician’s Guide to Teaching Mindfulness”, which became required reading for numerous mindfulness teacher programs around the world. Dr. Subramanian had the pleasure of undergoing training in MBSR and other mindfulness courses with Dr. Serpa and Wolfe at the VA. Dr. Wolfe also wrote another book, “Outsmart Your Pain” on practicing mindfulness for chronic pain, which will come out in the Spring of 2021. We sat down with Dr. Wolfe to learn about mindfulness, pick her brain and learn how it can help PWP as well as their caregivers.

Myth #1: We are in the middle of a pandemic and the last thing I need to be thinking about is being mindful

Mindfulness is the practice to intentionally bring awareness to the present moment so we can choose our response to what is happening; instead of acting on autopilot.

Now more than ever, it is critical that we harness these practices to help ourselves and the world. Mindfulness acts here like a flashlight; we point it at our habitual behaviors so that we can reconsider them and act in a different way. Without awareness, we can’t change what we’re doing. Awareness is always the first step.

a) Stopping automatic behavior

What are the behaviors that we are being asked to stop to avoid infection or its spread?

avoid touching the face, especially the mouth, nose and eyes

cough and sneeze into the elbow or a tissue, not the bare hand

avoid shaking hands or hugging

Practice:

Here is an exercise on how to practice this with the example of not touching your face:

Take a minute or two to notice every impulse to touch your face. Can you just observe the impulses and not act on them? What happens to the impulses when you don’t do anything? If it’s hard to not follow an impulse, imagine that you will leave a black marker-dot or glue on your face where you touch it. Feeling your breath like an anchor might be helpful to hold steady with the attention through the exercise.

Try to remember the exercise and what it feels like to not act on an impulse throughout the day.

Often you will only become aware while you touch your face. That is more awareness over not even being aware of touching the face and a sign of progress! Keep going!

Repeat Step 1 several times until you become more aware of the impulses during the day and it becomes more natural.

b) Choose a better behavior

Positive behavior patterns such as washing hands often and longer (about 20 seconds), to practice social distancing (6 feet if in public or work from home!) if possible or at least stay home with cold and flu symptoms, have been shown to decrease the risk of contamination and spread of viral infections.

Practice:

Mindful hand washing

Mindful hand washing is a practice introduced into hospitals and other medical settings many years ago. It’s used as a kind of mindful break, a moment when one is fully present with all the senses that involve the washing of the hands, like feeling the warm water and the slipperiness of the soap, or smelling the scents. This serves the double purpose of

i) getting the time in needed to clean the hands not only of dirt but also of bacteria and viruses, and,

ii) it serves as a mindful mini-break to reset the nervous-system during a stressful day.

c) Regular mindfulness meditation boosts the immune system

Several studies show that regular mindfulness meditation practice lowers overall stress levels, enhance quality of life, and boost the immune system.

d) Mindful media practice: Stay informed but don’t panic

Mindfulness practice also has a proven track record of lowering anxiety and worry. With all the media coverage of the coronavirus from around the world, it’s easy to drift into worry or even panic-mode.

Mindfulness helps us to be aware of the presence of anxiety or worry in the form of thoughts and as sensations in the body, and to observe them with friendliness— instead of trying to push them away. Repeatedly returning to the sensations of the breath or the grounding feeling of the feet on the floor help us to reorient to the present moment instead of racing toward some anticipated future event(s). As the slogan goes: Keep Calm and Carry On. That slogan, was designed and made popular during World War II to instruct British citizens on how to behave in the face of threatened massive air attack during the Battle of Britain.

Using the principles of mindfulness, we can practice this and help us all to move through the pandemic with all its unpredictability, doing our part to lower the spread and impact of COVID-19, physically and emotionally. It’s paramount that we use — and deepen — our practice to help ourselves and the world to stay calm and get through this together.

Myth #2: I am too busy to take time for mindfulness

There is a sense that meditation requires a huge investment of time but meditation actually saves time: When we meditate, we sit in silence until we know what really needs to be done and how; and then we have the clarity and energy needed to act. We are motivated to take action and our actions will require less effort.

7 reasons why meditation saves you time during the day

It slows down your sense of time. When you meditate your focus on one moment at a time. Instead of being lost in thoughts or on autopilot, you suddenly have many moments at your disposal. Giving yourself the luxury of time to meditate — Time to feel the breath, to slow down, even to be bored – you remember this sense of time during the day, which otherwise might be dominated by the feeling of “I don’t have time.” Instead, you notice that you have time to pay attention.

Spending time in formal meditation every day will make you spontaneously more mindful outside of meditation, meaning you will be aware of more moments during the day.

Beginner’s mind (being open to experiencing things as if for the first time) allows you to activate parts of your memory for “first time experiences”. Remember the first time you drove a car by yourself? Don’t you remember it like it took a long time? We are so awake and present for the first time we do something. We use all of our senses and attention for it so that we do get a lot more information bits in, which in turns makes us feel like it takes longer. When we do things over and over the “first time” attention is lost and we switch into autopilot mode.

Meditating will activate your parasympathetic (or “rest and digest”) part of the nervous system. This helps you recharge your batteries so you can handle time demands and other stress in a better (and usually more time efficient) way.

Meditation helps you to appreciate things more in the bigger picture, which makes you more relaxed as you deal with them. You make better decisions and get them done better and more efficiently. Plus, some of the items on your list will drop off since you will realize that they are just not worth your time and attention.

All of the above will help you get back into creative mode (being stressed and burned out stifles creativity), which is a state of flow, spaciousness and playfulness.

In meditation you cultivate equanimity. You learn to not resist moments of discomfort and to let them just disappear by themselves. This means they will pass by a lot faster, which in turn gives you more time in the day to pay attention to things that are more pleasant around you.

A big bonus point: Meditation time counts as sleep time. If you are afraid to take time away from your already reduced sleep time: do not fear. Your brain wave activity in meditation will move into a similar pattern as in light sleep which can be very restorative.

Myth #3: I am a caregiver. Mindfulness and equanimity practices are too complex for me

“Go placidly amid the noise and the haste and remember what peace there may be in silence.” I love this quote from German-American writer Max Ehrmann in “Desiderata.” Equanimity is like the eye of the storm; the calm center grounded in the knowledge that everything is constantly changing.

What is equanimity, and how can we invite more of it into our lives? Equanimity is being willing and able to accept things as they are in this moment—whether they’re challenging, boring, exciting, disappointing, painful, or not exactly what we want. Equanimity brings calmness and balance to moments of joy as well as to moments of difficulty. It protects us from an emotional overreaction, allows us to rest in a bigger perspective, and contains a basic trust in the course of things. The mature oak tree is another symbol of equanimity. Firmly rooted in the earth, it’s not moved by the changing seasons and weather patterns. The tree owes this stability to its taproots, which anchor it securely so that it’s stable but not rigid, even in strong storms. Equanimity is vast enough to hold all sides of life in a caring embrace.

Equanimity should not be confused with indifference. Equanimity is sometimes referred to as the “grandparent feeling.” Grandparents often have the same love for their grandchildren that they had for their own children, but with more ease and perspective around expectations and difficulties. As one grandma expressed it, “All these troubles will come out with the wash.”

Practice:

When A Loved One is Suffering

It’s difficult to endure when someone we love suffers. Often, we take on their suffering as our own. We get caught up in feelings of guilt that we cannot help more, or we believe we need to feel bad, too, out of a sense of solidarity.

This exercise, which was inspired by the psychologist Kristin Neff, helps us find equanimity when a loved one is suffering. The essence of it is the insight that ultimately we cannot make someone else happy. We can only work with our own minds and reactions and make our own decisions.

Repeat the following sentences quietly during meditation and also during the day:

“Everyone is on their own life’s journey.”

“I am not the cause of your suffering (or not the exclusive cause).”

“It isn’t in my power to end your suffering, although I would like to if I could.”

“Moments like this are hard to endure and yet I will continue to try to help where I can.”

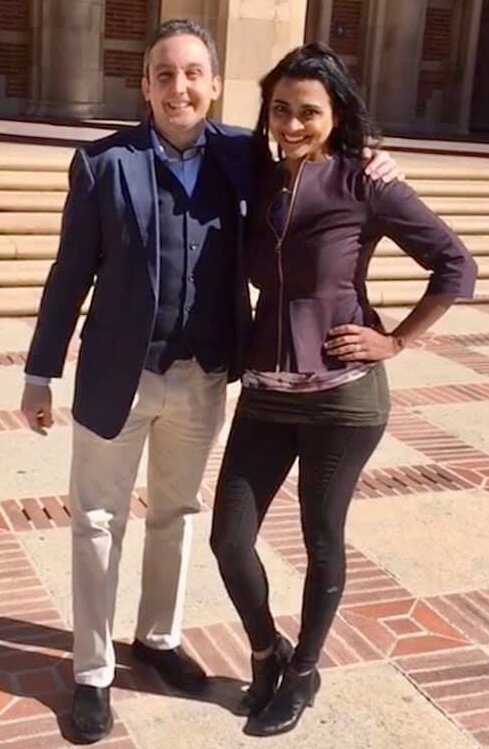

DR. WOLF WITH Trudy Goodman AND Sharon Salzberg

Myth #4: I am too agitated these days to be mindful, I can only practice mindfulness when I am calm

What if someone pushes your buttons? What if someone provokes you with their comment, hurts your feelings or if you feel challenged in your opinion?

Bringing awareness to how we feel goes a long way in practicing mindful habits. When we are feeling reactive we are so much more likely to respond in a way that is out of alignment with what we value.

How do we know we are being reactive? This is a great mindfulness practice right there, whether it’s around something that somebody said or other areas of life. For me, my shoulders tighten and I feel a pressure on my chest. My thoughts around the topic speed up and are usually not kind. I might feel defensive energy rising up from my belly into my chest. I feel ready to pounce, literally and figuratively.

Practice:

STOP

You might have heard of one our favorite acronyms to support being in the present moment:

Practicing S-T-O-P or simply taking one or two deep breaths in moments like that can help to break the reactivity cycle.

S – Stop, T- Take a breath, O- Observe, P- Proceed.

Maybe say it out loud or just to yourself: “Reactivity. This is what being reactive feels like.” Create a little space with your breath and then return to your intentions.

Myth #5: I am in so much pain that I can not possibly focus on being mindful

DR. SERPA AND DR. WOLF AT WEST LA VETERANS ADMINISTRATION

watch the PMDAlliance episode with Dr. Serpa YouTube recording

What we call pain is actually a conglomerate of three components: the actual physical sensations, the emotions we have about the pain and the meaning the pain has for us— and for our life, which we call “the story”. They are lumped together in our experience as if they only coexisted together in a box labeled PAIN.

Let’s imagine we would give the sensations, the emotions and the story each the value of 10. This box and its confinement would be like multiplying the power of its content: 10 x 10 x 10 = 1000. Of course, this is easily overwhelming and many people will try to never look into the box anymore. They just try to avoid the box at all costs.

Mindfulness is an open field

Mindfulness – which you could also call loving awareness — gives us a different approach to work with the content of the box. It helps us to open it up and take what’s in there out into the light. We take the contents of the box out into the open field that mindfulness provides. We turn toward the pain instead of away. We stop either running away or fighting it. We open the door to acceptance in a kind and accessible way.

We can now look at each of the three components of pain separately: The physical sensations are different from the emotions I have about the pain, which is different from the story I tell myself about it. Of course, they all intimately influence each other. But once I know that they’re not the same I can start working with them separately and they become much more manageable. I can simply feel into the sensations for what they are. How strong are the sensations? What are the main qualities right now? Stabbing? Tearing? Pressure? Heat?

I can feel what emotions I have about the pain in this moment, and once again in the next moment. Is it sadness or more frustration? Anger? Fear?

And I can see how the story, the meaning, deeply influences both how I feel about the pain and how I actually experience the unpleasant sensations.

Breaking the components down decreases the ping-ponging back and forth, with its dangerous potential to spiral out of control. It becomes more like a 10 + 10 + 10, which equals 30. I might not be able to handle 1000, but I can handle 30.

Practice:

Turn toward the pain and break it down

If you feel like you can work with the pain, do a quick inventory: How strong are the sensations? The emotions? The story (mental worry)? Which of the three is predominant? If the image works for you, picture a pie chart. Right now, which part has the biggest slice of pie? Work with that one.

Sensations: Place attention on, or “feel into” the physical pain. Does imagining breathing into it help? Be curious and specific. Stay with what’s there now, not what was there last time or five minutes ago.

What is the exact size of the pain? How much of the body is NOT in pain? (I once worked with a student with severe back pain who realized that the pain he experienced as debilitating was just the size of a quarter coin – while the rest of his body was pain free. That was a big breakthrough for him.)

Where is it located? What are its qualities? Is it sharp, rough, dull, burning, pressing, flashing, undulating, stabbing, tearing? If you relate to scales: What intensity does it have on a scale from zero to 10 — zero being no pain and 10 the strongest pain you can imagine?

Stay with the sensation in this way as long as you find it helpful. Experiment with softly naming to yourself what you find. Pay particular attention to change over time. Unexamined pain often feels it’s unchanging or always present. Prove that wrong— by paying attention.

Emotions: What are the emotions related to the pain? Work with the most obvious ones but be open to allowing them to shift and change. Feel them in your body and softly name them. Allow them to be here –not because you like them, but because they are here.

If you know the practice, work with the RAIN acronym:

R- Recognize

A – Acknowledge, Allow

I – Investigate with kindness

N- Non-identify

It can be very helpful to use the sentence: “This is what anger feels like, “…what fear feels like,” “…what sadness feels like.” It’s just an emotion that every human being feels at times. It is not who you are.

Some of our favorite mindfulness teachers include John Kabat-Zinn, Jack Kornfield, and Sharon Salzberg.

Dr. Serpa/Dr. Wolf sent us this list of resources for those who want to expand on the practices he shared:

Guided Meditations:

Sense and Savor walk

STOP Practice

Stop, Take a breath, Observe your experience, Proceed

Beginning a Mindfulness Practice

This blog is brought to you by Michael S. Okun and Indu Subramanian.

To read more books and articles by Michael S. Okun MD check Twitter @MichaelOkun and these websites with blogs and information on his books and http://parkinsonsecrets.com/ #EndingPD #ParkinsonPACT #Parkinsonsecrets and https://www.tourettetreatment.com/

He also serves as the Medical Director for the Parkinson’s Foundation.

To see more on Dr. Indu Subramanian she does live interviews of experts in Parkinson’s for the PMD Alliance. The topic of Music and the Brain will be the topic of this week’s episode on October 30, 2020- register here to attend the interview of Dr. Brodsky by Dr. Subramanian.